Reduced demand is just as important as induced demand

Note: Public Square editor Robert Steuteville is on vacation this week, and some popular past articles are being featured.

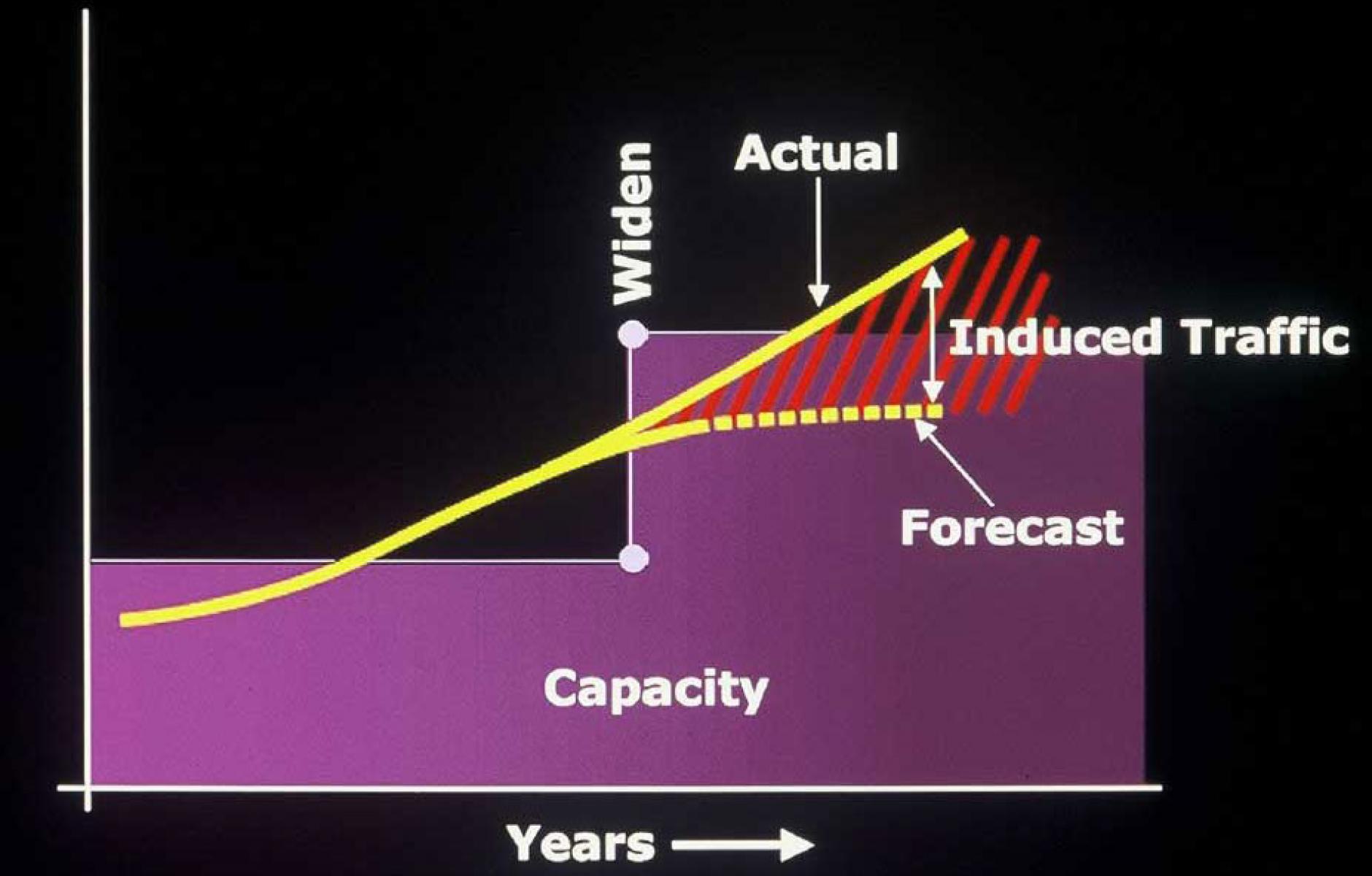

Induced demand is a well-known and generally acknowledged principle of road building, and may be summarized by the famous line from movie Field of Dreams: “Build it and they will come.” When substantial new road capacity is built, people will change their behavior—perhaps moving to a community further away from employment, taking advantage of the temporary excess road capacity. Over a few years, that excess disappears, and the new, bigger roads are just as congested as before—maybe decades in advance of when traffic studies had predicted the capacity would be exhausted.

In Walkable City, Jeff Speck describes induced demand as a “great intellectual black hole in city planning, the one professional certainty that everyone thoughtful seems to acknowledge, yet almost no one is willing to act upon.” That was 2012, and a growing number of transportation planners are willing to act upon induced demand. Not enough, but a growing number.

There is a concept that goes hand-in-hand with induced demand that transportation professionals rarely acknowledge exists, let alone act upon. It is called reduced demand. If road capacity is reduced, people will also change their behavior.

Walkable City also mentions reduced demand, which is “what happens when when ‘vital’ arteries are removed from cities. The traffic just goes away,” Speck says. People may stop making certain trips, condense multiple trips into one, use alternative transportation options like walking, biking, or transit, or travel at different times of the day.

Reduced demand explains why “carmageddon” never occurred in numerous historical instances where traffic capacity was suddenly eliminated. For example, a 60-foot section of the West Side Highway in Manhattan collapsed in 1973. The highway carried 80,000 vehicles a day. A city traffic engineer at the time, Sam Schwartz, was tasked with measuring the impact on the vehicles on nearby city streets. To his amazement, about half of the traffic could not be found at all on nearby streets, and the rest was absorbed without major impact on the city’s grid.

People made personal transportation choices to adjust to the new reality. The highway was never rebuilt—instead a surface boulevard was constructed, with much better results for the city.

Reduced demand is not just a New York City phenomenon, it seems to occur nearly anywhere. The literature on reduced demand is substantial—Wikipedia cites 150 sources of evidence—yet if anything, this phenomenon is less acknowledged or acted upon than induced demand. The denial of reduced demand has real world consequences, especially in the growing trend of freeway removal in cities. Over that last few years, this trend has accelerated across the US. Two major projects have been completed, four are underway, and two more are committed.

Without exception, these particular projects are beneficial. The freeways have substantially damaged their cities and either served no important purpose and/or alternate routes are available. Replacing these freeways with boulevards or street grids is repairing a wound in the city.

Yet there has been an ongoing problem. Engineers tend to design replacement thoroughfares that are too wide, lacking the qualities of good urban streets, creating ongoing barriers in the urban environment. Such thoroughfares are better than a freeway, but worse than what could have been. See the image at the top for the proposed replacement of I-375 through downtown Detroit, Michigan. This surface street is billed as a boulevard, yet it is nine lanes wide at intersections. That's nearly 100 feet of asphalt for a pedestrian to cross.

Another example is the proposed replacement for I-81 in Syracuse, New York. This road is supposed to be a “community grid”—in reality it is more like a suburban arterial thoroughfare that will do less than it should to promote walkable urbanism. (This is a proposal, and the city and state have a chance to improve the design.)

A similar process is unfolding in Buffalo, New York, where an enormous elevated highway, The Skyway, is coming down. There are two options, but even the better of the two should be placed on a diet. That is a “boulevard” with a design speed of 40 miles per hour (some traffic would go faster), and multiple on-and-off ramps, to accommodate all of the traffic that currently exists and rush it through the city. That's not an urban street, it is an urban highway. I don't include an image, because the state didn't provide any good ones, rather obscuring the true dimensions of the proposal as text within a large report that most of the public will not read or understand.

I am a supporter of highway removal, but whenever I see this it breaks my heart. It’s not a question of lack of resources. I could live with that. Overwide roads cost tens of millions of dollars more. And what is the reason? Engineers feel compelled to replace every bit of capacity that they are taking away on the principle that “carmageddon” will result from a smaller street. They ignore or disbelieve the idea of reduced demand. They likely acknowledge induced demand, but not the reverse. What goes up, does not come down. They also ignore the remarkable ability of a street grid to absorb traffic.

The corollary to Field of Dreams is this: If you don't build it, they will not come.

You really don’t believe in induced demand, if you don’t also believe in reduced demand. Traffic engineering/planning is going on a hundred years as a profession. It’s time to learn from history, to believe the science, to get smart about street design, to fully use the idea of reduced demand where it has the potential to improve a city's economy, society, and mobility.

No comments:

Post a Comment