A typical neighbourhood in Dubai. Source: Google Images

A typical neighbourhood in Dubai. Source: Google Images

There are great attention ongoing on Dubai.. Dubaization, as many would call.. The city that emerged from the sand dunes to be one of the top worldly megacities within less than 25 years.. Yet; many observers mistakenly analyze what is happening within the tiny City-State context..!!

Metropolisation and Spatial Segregation in Gulf Cities:

The Case of Dubai

Since antiquity, Bedouin cities have always been influenced by sedentary culture, which has underpinned the social sustainability of tribes per se. The traditionalist ‘compact-city’ planning had high density urban structures with mixed land uses. Cities like Abu Dhabi, Dubai & Kuwait City have seen an expeditious transition in the last 50 years. They have become highly car-dependent, exclusionary in nature and their planning and development patterns have been largely shaped for a certain class. The critical intersection of urbanisation and economic development often leaves behind the traditional purpose of streets (making social connections). While over time, mass migration has brought about de facto cosmopolitanism in Arabian cities, especially Abu Dhabi & Dubai; foreign residents continue to experience segregation. The idea of putting a modernist urban grid into an Arab context has had various implications on social life. The dead building facades & obstructing boundary walls of houses that limits ‘eyes on the street’, in addition to segregated land use zoning, a lack of pedestrian-centric infrastructure, and dependence on motorised transport, have painted a car-centric image of Abu Dhabi’s public life. Howbeit, the average superblock size is 900×600m, which has high potential for more accessible and effective street use. In a general sense, spatial segregation intensifies social segregation. Streets, being the most critical unit of a neighbourhood, can be used to include or exclude communities. This dimension requires particular attention, and is addressed here through the empirical study of Deira, a neighbourhood in Dubai. The assessment revealed that various characteristics relating to urban form, such as built-up density, land use, mobility, streets layouts, built environment’s safety and aesthetic qualities, are the main factors undermining social sustainability in the studied locality. The results informed a set of suggested regeneration strategies for the neighbourhoods. These include increasing the built-up density by redevelopment, vertical mixing of land use to achieve diversity in housing types and access to public transport.

It is essential to understand the critical intersection of urbanisation and economic development in growing economies. After the 1970s, the emergence of the oil industry precipitated a notable rise in demand for labour. In order to fulfil this, the Kafala system was established. It promoted the rapid influx of migrant labourers (both skilled & non-skilled) largely from South Asia. As a consequence, Emirati cities witnessed the emergence of a hierarchical society where locals were part of a privileged social category, while migrants occupied the lowest strata. This form of otherisation has aggravated social inequalities and segregation.

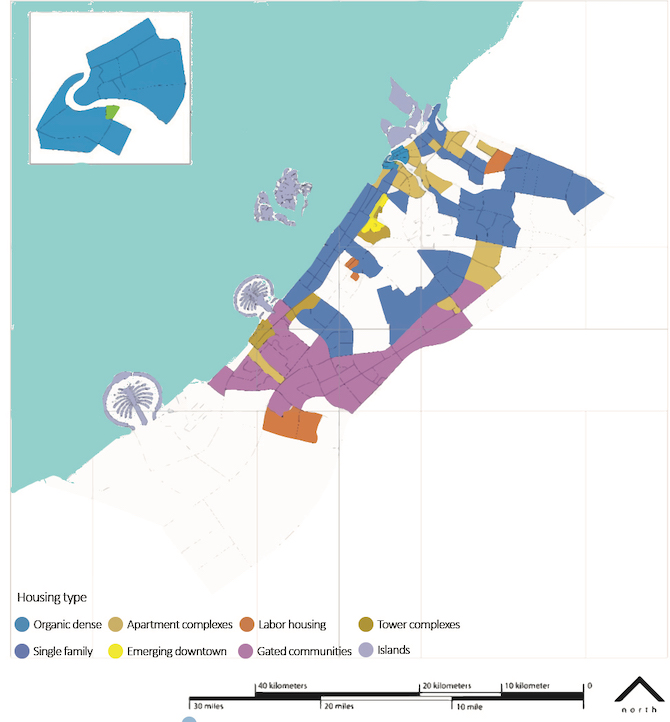

Morphology has long been a useful tool for understanding and analysing affordability and diversity. Research studies on the morphological evolution of cities have focused primarily on more established societies with longer histories. Spatial analysis of urban form has not been historically contextualised when it comes to the UAE or Gulf region. To select the case study, a few parameters were taken into consideration, including: housing type, rent pricing, access to public transport and other urban services. There are currently seven different types of housing: organically dense, tower complexes & waterfronts, island & off-shore communities, apartment complexes, midrise labour colonies, gated communities & single-family apartments.

Housing Type

Due to the discovery of oil, the sudden influx of capital called for a new master plan by Harris in 1971. The new plan clearly represented modernist planning principles and called for ring roads around the city core and a radial street network to the low-density suburbs. The growth period of 1971 to 1993 is categorised as a suburban growth phase wherein single-family communities emerged as a development pattern. In 1968, the government implemented the National Housing Scheme, which granted land to citizens free of charge. The institutionalisation of the National Housing Scheme has contributed to suburban growth and sprawl, characterised by a repetitive landscape with dormitories and gated communities on the fringes of the city, such as labour colonies. The housing landscape is clearly fragmented and for the most part, is deemed unaffordable.

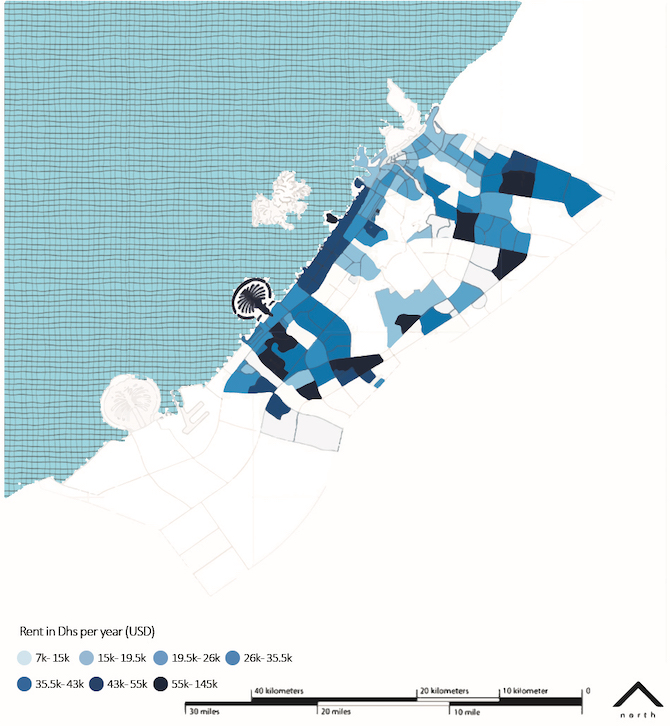

Rent Pricing

The second phase of Dubai’s development called for the provision of a road system; zoning of the town into areas marked for industry, commerce and public buildings; areas for new residential quarters; and the creation of a new town centre. Newer developments such as Dubai International City and Silicon Oasis were also marketed to the middle-class population. Today, areas featuring the apartment complexes & mid-rise pattern are among the most affordable areas for Dubai’s middle-class population (whose mean income is 30,000 to 66,000 USD per annum) with rental prices ranging from 6800 to 43,500 USD/year.

Upon juxtaposing the affordable rent pricing with housing types, it becomes clear most migrant populations live on particular land parcels, which are organically dense or mixed land use apartments.

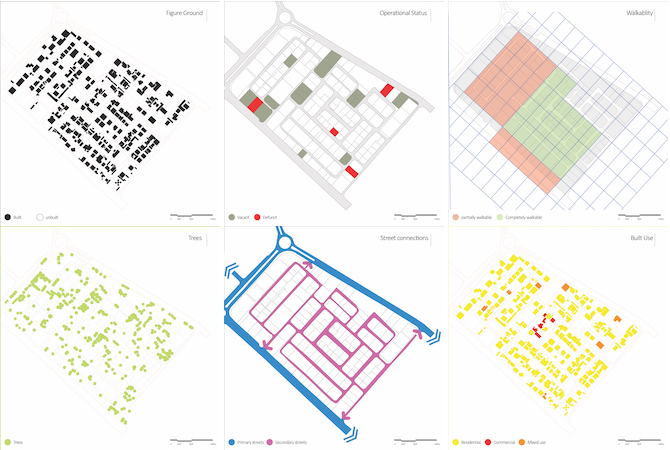

Hence, in order to further investigate, Al Mamzar was taken as a case study, as it falls under the single family structure typology and has lower rents with a considerable migrant population. The neighbourhood was assessed on few parameters; volume, walkability, tree density and functional use. 27.8% of the site comprises its built environment – the rest is open under-utilised space. There are 13 vacant & defunct plots, indicating the infill development potential of the site. Upon overlaying the average walkable grid of 800m perimeter, almost half of the neighbourhood is completely walkable & half is partially walkable, with 32% tree canopy with 25 trees/hectare.

With well-connected street networks & fine urban grain, the neighbourhood seems to be inactive most days of the week (except Fridays), one of the reasons being its predominantly residential use. Through the site study; site mappings, user surveys and analysis, a number of inferences can be drawn. Firstly, the location of Al Hamriya port & toll road affects the neighbourhood’s primary entrance. Pedestrians are required to take longer routes to enter. Secondly, the absence of pedestrian infrastructure (car-free zones, cycle tracks, parks etc.,) along with stringent land use regulations, makes the neighbourhood less appealing. The latter fails to offer different choices to its inhabitants in terms of recreational activities, such as shopping. The function of streets depends on the activities that take place on them. Indeed, the relationship between pedestrian and vehicular movement, parking lot locations, defunct buildings, transit infrastructure, and land use policies, contributes to shaping the urban environment. Future research on such secluded neighbourhoods can help us understand how pedestrian infrastructure, such as cycle lanes, parks and public space, and mixed-land use, can make a place more vibrant and contribute to pedestrian visibility. The relationship between urban form and spatial segregation is labyrinthian, although low density development patterns can contribute to more segregation. Inclusive housing types with affordable rent pricing have a greater potential to reduce segregation. On the contrary, higher population densities could lead to greater integration if neighbourhoods include more multi-family housing types. Finally, comprehensive and consistent data on the impacts of local land use regulations should be collected to inform future research and planning practice.

With well-connected street networks & fine urban grain, the neighbourhood seems to be inactive most days of the week (except Fridays), one of the reasons being its predominantly residential use. Through the site study; site mappings, user surveys and analysis, a number of inferences can be drawn. Firstly, the location of Al Hamriya port & toll road affects the neighbourhood’s primary entrance. Pedestrians are required to take longer routes to enter. Secondly, the absence of pedestrian infrastructure (car-free zones, cycle tracks, parks etc.,) along with stringent land use regulations, makes the neighbourhood less appealing. The latter fails to offer different choices to its inhabitants in terms of recreational activities, such as shopping. The function of streets depends on the activities that take place on them. Indeed, the relationship between pedestrian and vehicular movement, parking lot locations, defunct buildings, transit infrastructure, and land use policies, contributes to shaping the urban environment. Future research on such secluded neighbourhoods can help us understand how pedestrian infrastructure, such as cycle lanes, parks and public space, and mixed-land use, can make a place more vibrant and contribute to pedestrian visibility. The relationship between urban form and spatial segregation is labyrinthian, although low density development patterns can contribute to more segregation. Inclusive housing types with affordable rent pricing have a greater potential to reduce segregation. On the contrary, higher population densities could lead to greater integration if neighbourhoods include more multi-family housing types. Finally, comprehensive and consistent data on the impacts of local land use regulations should be collected to inform future research and planning practice.

This piece is part of a series on urban development and the role of road infrastructure in forging socio-spatial conditions, based on contributions from participants in a closed LSE Roundtable in September 2021. Read the introduction here, and see other pieces below.

In this series:

- (Re)thinking Streets in Low Urban Densities by Alexandra Gomes, Apostolos Kyriazis, Clémence Montagne & Peter Schwinger

- The Future Development of the City of Kuwait: Kuwait’s Urban Form as a Case Study by Roberto Fabbri

- Pedestrian Dynamism Index: An Approach to Increasing Permeability between the Peripheral and Central City of Guadalajara by Monica Castañeda, Ricardo Fernandez and Roberto Robles-Arana

- Studying Abroad in Stockholm: Incentivising Young Adults Towards Greener Mobility by Ningning Xie

- Plan with a Purpose: A Systems Approach in Transportation Development and Liveable Cities by Lizao Chen

- Metropolisation and Spatial Segregation in Gulf Cities: The Cases of Abu Dhabi and Dubai by Moiz Uddin

- Rethinking Streets in North Obhur, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia by Alok Tiwari

- Safe and Active Mobility: A Prototype for the Re-Pedestrianisation of Residential Neighbourhoods in Oman by Gustavo de Siqueira, Ruth Mabry and Huda Al Siyabi

- Urbanisation and Physical Activity: Addressing the Needs of Omani Women by Ruth Mabry and Huda Al Siyabi

No comments:

Post a Comment